Content Advisory: ICE, immigration, state violence, injury, weapons.

NOTE: You may notice some shifts between present and past tense in this piece. I considered going back and unifying the text, but the tenses also reflect how I experienced both the events described, and the process of writing about them.

I’ve been a bit shaken all day. My mind feels kind of scattered, likely the result of poor sleep. A buddy of mine looked at me and said, “You’re still in fight-or-flight mode. You’re going to be for a while.” He’s probably right. This is not what nervous system regulation feels like, but I want to share my experience while it's still fresh. I've avoided news reports and videos and livestreams as much as I can because I want to capture my own experience, as purely as I can.

I was at 411 W. Cataldo yesterday from approximately 2pm until after midnight. This is what I experienced, recalled to the best of my ability.

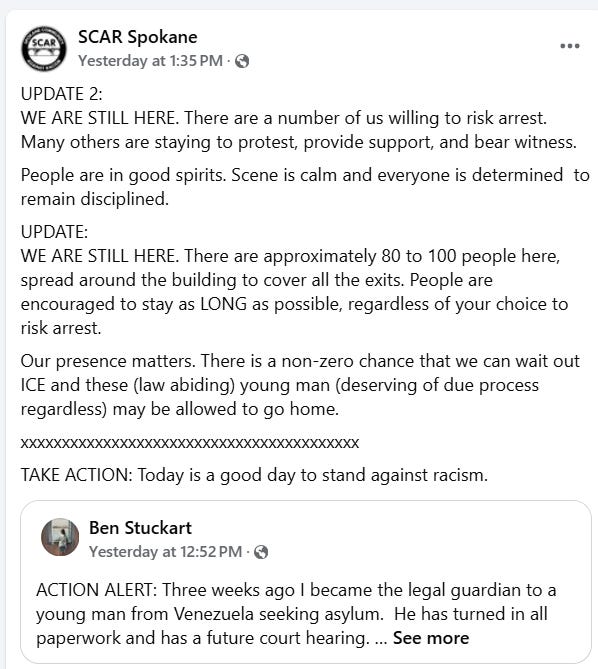

I am Co-Executive Director at Spokane Community Against Racism. Around 1pm on Wednesday, I went into work for my schedule office hours, planning to tackle a few tasks in preparation for Spokane’s PRIDE Festival this Saturday. I had just set up my computer when my phone buzzed. An alert in a group chat directed me to a Facebook post by Ben Stuckart. In it, Ben explained that he was the legal guardian of Cesar, a Venezuelan asylee who was illegally detained by ICE at his scheduled check-in. "I'm going to sit in front of the bus,” he said, “Feel free to join me…."

I re-posted the status almost immediately and began chatting over my own potential participation with a colleague in the office. But after only a few minutes, something clicked. This was an invitation to material action to stop a government kidnapping of a lawful asylum seeker. After helplessly listening to accounts of these detainers for weeks, grieving the integrity of my federal government, and raging against the lack of due process—after weeks of desperately wishing I could do something about the violent injustice happening in my country, I was being handed the opportunity to take action.

I took a beat to consider my position, and decided I have the social, financial, familial, and personal stability to risk arrest by taking a stand. My principle of solidarity with the oppressed means I cannot hoard the privilege capital I acquire, I must spend it in defense of those more oppressed than myself. I decided to go.

The Beginning

I arrive at 411 W Cataldo at just minutes to 2pm. There are protesters waving signs on the corner, drawing supportive honks from the cars racing up Washington. I ask one sign-waver if they knew what “the plan” was and they tell me to direct my questions to the people demonstrating by the minimally marked white bus up the hill.

At the bus I see about forty people standing along the walkway or sitting in the grass outside a red brick building I had driven past a thousand times, never knowing it was home to Immigration Customs and Enforcement in Spokane. People are filled with classic protest spirit: that unique mix of upbeat, almost jovial energy, mixed with grim determination and hope. Ben is up there, milling about and taking phone calls near the stark white ICE bus. Ben was accompanying Cesar to his scheduled check-in with ICE—a regular part of the asylum-seeking process for people fleeing violence . Instead of honoring Cesar’s lawful compliance, ICE detained him without due process and prepared to transfer him to a detention facility in Tacoma.

No one is really “in charge,” but there is sense of loose order, provided by rapid response observers from the Washington Immigrant Solidarity Network (WISN). The sense of order heightens with the arrival of more regular faces from Spokane’s progressive movement scene: perennial volunteers, leadership and members from the Peace and Justice Action League of Spokane, Spectrum Center Spokane, The Way to Justice, Mutual Assistance Survival Squad, Veterans for Peace, and more fill the grass. A representative from the Washington State Commission on Hispanic Affairs is present, along with Spokane City Council member Lili Navarrete and former State Representative Timm Ormsby.

A uniformed ICE agent briefly emerges to demand we keep the sidewalk clear from the building entrance to the bus doors, and we comply. Our goal is to keep ICE from transporting the asylee under Ben’s legal guardianship—a twenty-one-year-old young man named Cesar Alexander Alvarez Perez—from being transported to Tacoma. We can keep the sidewalk clear, but we don’t plan to allow the bus to leave.

We’re activists, advocates, and organizers—so we start organizing ourselves. We take turns on two white bullhorns addressing the group for a few minutes each. Some speakers share situational updates (“Did you see the GEO Group insignia on those uniforms? That’s the for-profit company that operates the Northwest ICE Processing Center (NWIPC) in Tacoma”). A couple other speakers share protest best practices. Another spreads the word that the ICE building is leased by Goodale-Barbieri; the phone number of a relevant corporate officer is announced over the bull horn, and we begin flooding their office with calls. We talk, we chant. We sing songs.

It becomes clear that there is some division over tactics, so we discuss what it means to be an observer versus a willing arrestee. Everyone is encouraged to make their own personal decision, and we collectively begin to define language about the type of protest we are a part of. We are disciplined. We are non-violent. We are not passive. We are not “nice.” Our goal is to prevent a government abduction, and to that end some of us are willing to engage in behaviors that carry the risk of arrest. Someone parks their car in front of the bus. Later, another person blocks it in from the back.

I am on the bullhorn, sharing what I know about civil disobedience, when a man with a face covering rides up on a bicycle, pulls out a can of white spray paint, obscures the front window of the bus. Then he rides away.

By 4pm, the crowd has swelled to around a hundred people. Members of the Party for Socialism and Liberation bring cases of water and some community members who cannot stay for the protest drop off snacks. The building is quiet, and no one has come out to disperse us or give orders, so we wait.

Building Pressure

At some point someone parked their car in front of the bus so it cannot be driven forward. Ben sits on the sidewalk in front of the bus doors, clearly in the area the ICE officer demanded we keep clear. Ben announces that he is willing to be arrested to prevent this government abduction. People begin to join him, seating themselves on the cement of the sidewalk. Someone else moves their car to block the bus from behind.

Eventually it occurs to everyone that ICE has likely given up on the bus. It is blocked in by two cars and the windshield has been permanently obstructed. If ICE is going to move Cesar, they will have to take him another way.

“Does this building have other exits?” someone asks. “Let’s send some people around to look.” A gaggle breaks off from the main group and discovers two more areas an ICE vehicle can leave from.

“Let’s cover every exit. We need people in each place.” The crowd by the bus thins to thirty or forty, as clusters break off to keep watch over the south gate, and the egresses in the building’s eastern parking lot. There’s still an active group of sign-wavers on two Washington intersections. Suddenly, a hundred people feels wholly inadequate for the job we’re trying to do, so I bury myself in my phone, furiously messaging friends and updating my personal and professional social media accounts to get more people to come down. I see many others doing the same.

Some time between 4 and 5pm, clearer roles have emerged. There are observers documenting why we are here. There are outward facing demonstrators near the roads, and protesters who have focused on the ICE building. We continue to developing smaller teams and leveraging our various skills toward our common goals: oppose ICE, stand up for due process, stop the kidnapping.

I have joined the willing arrestees seated in front of the bus. Perhaps because I have the most (professed) organizing and protest experience in the group, or perhaps because I cannot stop nervously strategizing aloud, I become the de facto group leader. I have a team now, and the wellbeing of the people who have decided to risk arrest with me are—at least to a degree—my responsibility.

During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s, people who wanted to engage in civil disobedience were often required to complete intense, multi-day training to learn about the arrest procedures, build group cohesion, and train themselves through study and role play to endure violence without retaliating. I, on the other hand, have only minimal training in the basics of civil disobedience. I cannot lead an impromptu training in non-violent protest, but I do have one experience to draw upon.

I have participated in civil disobedience once before at the No DAPL protests in South Dakota. My mentor at the time took a small group of us to the Prayer Camp at Oceti Sakowin. When the protest leaders told us to, we advanced down the main road, marching until law enforcement officers, in full riot gear, chased us back, beating their shields in rhythm and yelling at us to “GET BACK!”

I still remember freezing for a moment, before another protester yelled at me to move, and I turned to run. I remember the acrid smell of the gas that quickly became an engulfing fog. I remember that I was part of one of the safest actions. Later waves returned with running eyes, wheezing lungs, and bleeding welts from rubber bullets.

I was a little shaken that day, but no one touched me. And I learned a lot from the organization at Standing Rock. I combine that learning with my nine years of organizing and advocacy experience in Spokane and discussed safety and tactics with my growing team.

“Do you have any kids, pets, or plants who will come to harm if you don’t come home on time tonight?” I ask, “Do you have an emergency contact who is not at this protest? Do they know how to care for your dependents? Do you need to call your job?”

We talk strategy, and adopt every choice collectively. We agree that we will resist, but we will not fight. We will not initiate any physical engagement, but we will put ourselves in the way.

Cam volunteers her legal knowledge and notebook, and I make sure each member of my team provides the necessary information to receive jail support. Sabrina and Angel step up to organize bail. Other volunteers off site act as trustees of information to ensure people’s emergency contacts are notified if their loved ones are arrested.

It is hard to overstate just how cared-for I felt by my community yesterday. Hundreds of Spokanites answered the call to stand against injustice, and we didn’t just come with signs. We came with signs, sharpies, and bullhorns; we came with cases of water, bags of chips, granola bars, and little oranges; we came with sunscreen, and masks, and med kits, and law licenses, and organizer training, and communications experience, and sheer commitment. We showed up for each other, so that together we could stand up for the people in ICE custody.

My team collectively agrees to stand and lock arms in front of the bus—or whatever vehicle ICE is using—to prevent ICE from putting Cesar on board. By now, another name was floating around the gathering: Joswar Slater Rodriguez Torres, a Columbian man in his early 20s. We now have two people to protect, and three or four different exits to guard.

An uneasy tension rises as people buzz around the building sharing updates of varied value. “Have you seen anything?” “No one has gone in or out.” “So many cars over here. Another vehicle there.”

Resistance

Some time after 4pm we hear a cry of alarm from the south gate. There are a couple hundred people distributed around the building now, and waves of us rush down the hill to respond. The gate on the south side of the building is open. It encloses a parking area for ICE vehicles, and one of them has its lights on.

I can only recall what happened next in bits and pieces. My team runs to the open gate and locks elbows to create a human barrier. We stand still as the mismatched contingent of five or six uniformed ICE agents stalk toward us. I feel my body being grabbed, and rough hands trying to wrench my arm from my teammate’s. An angry cacophony of “MOVE! Get out of the way! Get out of here!” fills my ears, as I am separated from my team and thrown to the side.

We reform the line and try to stabilize together. I feel hands shove me in the back and the shifting weight of my teammates as we try to ride the waves of shoves, yanks, and strikes. The agents seem to have chosen individuals to target, and as one friend hits the ground, I am pushed over her from behind. Somehow, it ends. The ICE vehicle and agents withdraw and close the gate. I have scratches on my palm, but I am proud.

We stood strong and prevented a vehicle from leaving the ICE facility. A few minutes later someone raises a pair of glasses in the air. “Did someone lose their reading glasses?” They are smudged and scratched, left on the ground from the physical confrontation. They are mine. I didn’t even realize I’d lost them.

The Hurry up and Wait

Anxious boredom. That’s the best phrase I can think of to describe the feeling at the south gate. Between twelve and twenty-one people stood or sat cross-legged in front of the last place ICE attempted to leave, prepared to lock arms and take tear gas and pepper spray if need be. Between ten and eighty observers stood watch, separated from us by yards of asphalt, and filing up the sidewalk, across the way. Handfuls of people ran back and forth between sites, passing supplies and messages, collecting personal effects, giving rides, and moving cars.

Sometime around the initial clash with ICE, I gave my phone to an observer for safe-keeping, and later arranged for it to be returned to my family. Later, a teammate kindly lent me their phone to text my husband and let him know I had not been arrested. I was okay.

My team stayed focused on the gate. If it was not personally affecting us or that gate, it did not matter. We planned to resist as a group. We would keep reforming the line as long as we could, but if we were fully separated from the line, we would accept arrest, and did not wish to be de-arrested.

We waited.

I coordinated with the leaders of the observers, primarily people affiliated with WISN and Veterans for peace.

We waited.

One team member, a therapist, led the group in moments of breathing and centeredness. “We are here for the people in that building,” this person said. “They need us. Send your love to them.”

We waited.

I onboarded people as they joined the south gate.

Jail support, emergency contacts, securing personal effects, removing weapons and jewelry.

“Our only chant is ‘Let them go!’”

“We are here to resist with disciplined nonviolence.”

“Can you take a punch without returning one? If not, do not join the line.”

We waited.

I coordinated with the leaders of the “ICE Out Now” protest, several hundred strong, which planned to meet at the Red Wagon. I wanted everyone fully briefed before they arrived on site.

We continued to wait, rubbing Vaseline around our eyes and periodically wetting face coverings with water.

I recycled announcements as more people joined us, and we waited.

A few times we heard loud pops, or a raised alarm from around the corner. We formed up immediately, pulling our masks over our faces as we locked elbows, but they never came to us. The main action appeared to be happening on the East side, where hundreds of us were gathered. Many south gate observers left to join them, but my team, and handful of observers decided to stay. If we left the south gate unattended, ICE would try again.

Pepper spray and tear gas wafted over to us on the wind, making us cough and raise our masks. Through the gate we could see one or two ICE officers continually watching us from the rooftop of the building. Drones buzzed above our heads. We stayed focused and we waited.

I felt like a stretched rubber band. We snacked, drank water, and took bathroom breaks. We shook out our bodies, we attempted to make small talk and get to know each other better. Two members of my team helped manage our emotional health with their therapeutic training. A few others furnished us with updates. I felt starved for information. We were blind on the south side, only able to see a small corner of the crowd, so we relied on information from runners.

Some updates were interesting: Negotiations with the mayor’s office, staff talks in city hall. Attempts to deescalate the situation through political channels. Other updates were disheartening: Another of our number arrested. Someone else injured. Some people from the east side came over to rest, show us their bruises, or display bleeding welts that looked like they came from rubber bullets. Conflicting rumors filtered down to us about whether ICE had moved Cesar and Joswar, and how many other detainees were in the building.

Occasionally, the updates were useful, and I would call over a runner or my counterpart from the observer side to make sure the information was acted on. Most often, the updates didn’t change anything. Spokane County Sheriffs on site, perhaps even deputies from Kootenai County in Idaho. Various numbers of SPD officers, SWAT teams, and threats of the National Guard. None of it mattered. Our mission was to hold the gate.

More tense boredom. Every few minutes curls of smoke peaking around the corner, the flash of a uniform, or a distant pop would make us all jump, and we’d jump into formation. We got a lot of practice forming up at a moment’s notice.

Backup

Some time after 7pm, we were wearing thin. ICE agents still observed us from the roof, but our lines of willing arrestees and observers had significantly thinned.

“Look! They’re coming! We have support coming!” The call came from the observer side. And there they were. Marchers from ICE Out Now demonstration, hundreds strong with signs raised high, they marched through Riverfront Park to join us.

“Gondor calls for aid!” Joked one person. Relief washed over us. We felt like the cavalry had arrived.

We also knew an influx of new bodies carried risks. I raced out to meet the sound wagon leading the march. I had been in periodic contact with the organizers of “ICE Out Now” throughout the day, and I was allowed to jump on the mic to give the crowd the same briefing I had given a hundred times.

I cannot remember my exact words, but I know I thanked them for being there. I was so grateful for their presence. I told them about our roles: observer and willing arrestee. I told them we were committed to disciplined nonviolence. I invited them to join the lines at the south gate on those terms, and proceeded to onboard the marchers who peeled off to risk arrest. The majority joined the east side.

The End

I don’t know how long it was before the second wave of tear gas came. It drifted over to us on the air, we could see crowd movement, and we braced to be cleared out, but nothing happened. Minutes later we heard that Cesar and Joswar had been removed from the building.

Rumors of their removal had been circulating all afternoon, so we continued to watch the gate. Later we learned, the second wave of teargas was used to clear the exit ICE ultimately used to load Cesar and Joswar into a Spokane-County owned van.

We were still being watched by drones above and ICE Officers on rooftop. We could see flashing lights from rows of police cars on North River Drive, and the surrounding police presence remained heavy, so we stayed.

The moon started to rise, and we discussed how long we were willing to wait. Were we going to wait out the police? Why were we still there if the detainees had been taken? Had our goals changed? No, we decided.

The abduction was wrong. The way law enforcement was treating us was wrong. We stayed to stand up for due process using our First Amendment rights. We had every right, perhaps even a duty, to remain at the gate. The presence on the east side continued to wane, and the law enforcement presence began to shrink. We caucused again, and sometime around 11pm we decided to do a final interview with KHQ in front of the gate, and head home.

We arranged to leave in pairs, carpooling and arranging rideshares. It was 1am when I finally made it home. I smiled when I saw my personal effects in the hall, carefully delivered to my family in a demonstration of community care and organizing in action. My phone was carefully tucked inside. When it was finally charged enough for me to turn it on, it was flooded with messages from friends and family asking if I was okay. **

Afterward

I started writing this the day after the events described, on Thursday evening. I had to stop writing after recounting the confrontation with ICE at the south gate. I originally started writing my narrative to process the experience, and to get the story out of me before it was tainted by too much external commentary. Now writing this has become important to me, a way to get my story on the record.